|

|

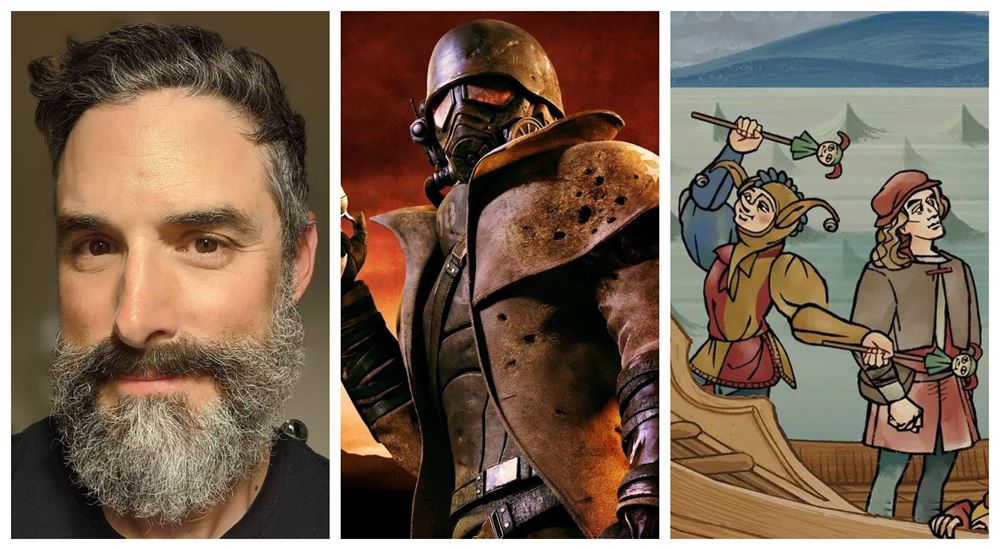

Josh Sawyer Reflects on Design Evolution: From Icewind Dale to Pentiment5/29/2024

Josh Sawyer is a name that has been familiar to RPG fans for decades. He's worked on Icewind Dale, Neverwinter Nights 2, Alpha Protocol, Fallout: New Vegas, Pillars of Eternity, and most recently Pentiment.

|

Josh Sawyer is a name that has been familiar to RPG fans for decades. He's worked on Icewind Dale, Neverwinter Nights 2, Alpha Protocol, Fallout: New Vegas, Pillars of Eternity, and most recently Pentiment. How did he get into game development, how has his design philosophy changed over the years, and why did he decide to do Pentiment a little differently? He answered all these questions for us during the GDS conference in Prague.

Your work is often associated with intricate narratives and designing complex systems. Could you discuss your design for these systems, and how did this philosophy evolve over the years?

Yeah, I do think it's changed. Initially, when I started working at Black Isle, the first game I worked on was Icewind Dale, even though it had a strong combat focus, it came right after Planescape Torment, which obviously was known for very big branching dialogues. And the studio in general, Black Isle and later at Obsidian, was very, very into big branching dialogues with a lot of question nodes you could loop through and lots and lots and lots of options, and also a lot of reactivity to your build choices and ways to complete quests that unlocked in that way.

And then that kind of migrated towards such a reliance on question nodes, not flooding the player with as many options, especially if the options felt superfluous, like they weren't really adding anything. And on New Vegas, one of the things that we noticed is, in contrast to Fallout 3, which had percentage-based checks. We went with flat checks, either you made it or you didn't, which on the one hand is good and it's satisfying that your build is rewarded, but also it was always clear, like I should always pick this option. So the role playing element kind of went away because it implied that if you ever saw your option come up, you should pick it.

This continued into Pillars and Deadfire because, at the time, they didn't have a super great idea of how to handle it. On Pentiment, the way I've tried to approach it is that there are almost never any question nodes. Every conversation has a through flow. It's about a thing, and you never reach a point where you're kind of circling back and looping. It has an arc that ends, and I feel like that makes the conversations feel much more natural. You can still put in all sorts of cool branching, but it's all sort of moving towards the end goal that you know as a writer when you start the conversation. And then the way that I've tried to handle using checks and dialogue is if you unlocked it, you can pick it, but sometimes it's not actually a good idea to do that.

In Pentiment, characters very often get aggravated when you pick those options. So you kind of have to think about the character and the situation that you're in and whether or not the character is going to respond positively or negatively to you sort of saying that thing. And I think that's a nice balance because the player is clearly being given more options because they're backgrounds, but they still have to role play and read the social situation to get the outcome that they want. And sometimes though they might say like, „I don't care about getting an ideal outcome, I want to pick this option,“ and that's totally valid as well.

Why did you decide to become a game developer?

I graduated with a degree in history, and I really didn't know what I was going to do with it. I thought I was actually going to become a tattoo apprentice. I was doing web design at the time, and I had done web design work for Steve's tattoo in Madison, Wisconsin. And I had also taught myself Flash animation to do their website. And when I applied for the job at Black Isle, or technically Interplay (since it was to work for Black Isle), I knew Flash animation, specifically Flash 3. And I remember very clearly that they said that out of 62 applicants, I was one of only three people that knew Flash. And I was not the first choice. The first choice they offered the job to decided to go with his girlfriend to Seattle. So thank you wherever you are.

But I got hired in part because I knew Flash animation and I was decent at HTML markup. And I knew a lot about Planescape. I knew a lot about D&D, like a lot about D&D. When I started working on the Torment website, I worked as closely asi I could with the designers, programmers, animators, and everyone involved because I was really into it. And I kept asking Feargus Urquhart, who was the head of Black Isle at the time, like, please let me do some design work. Like I love doing this stuff. As they began development on Icewind Dale, someone on the team left, and Ferg said, 'Okay, you can do this half-time. We still would need you to do websites. ' Because I was familiar with it, I did the Baldur's Gate 2 website. I actually did the initial Neverwinter Nights website for Bioware that was only around for like six months or whatever. But they still wanted me to do my web work, but they're like, but you can also do design work on Icewind Dale. And it was partially, I think, because I just knew the Forgotten Realms and I knew D&D very, very, very well. And that's where it took off.

As a fan of D&D, what was it like to bring the world of D&D to life in Icewind Dale?

It was crazy. When I started, I really didn't know anything about development. Right away, I was thinking, 'I want to do this and I want to do that,' but people were like, 'You can't do any of that. That's not how this works.' I had done level design in Hammer and Radiant, I think, which were Quake editors. So I was super into Quake and my levels were bad, like super bad. But I knew about that aspect of game development, but that was very, very different from working on Icewind Dale.

Initially, I was super enthusiastic, and there was a lot of, 'Okay buddy, you've got to calm down. We can't do any of this stuff.' I remember very clearly the first level that I designed was Kresselack's Tomb in Icewind Dale. I drew the map on a large piece of newsprint and gave it to Dennis Presnell, who is still at Obsidian. He modeled it, and it turned out to be a fun dungeon, but it's awful to navigate. So I learned that a top-down map is not the same as an isometric map.

But then I tried bringing in all of my D&D and Forgotten Realms lore to expand the world. I did all the unique magic items in Icewind Dale 1 because I was super into the lore . I had the Magister supplement for Forgotten Realms and all the other books that featured those super special unique items. So I wanted to bring that flavor to the unique items, which I really thought was a cool aspect of D&D.

And then the other thing is there were so many other spells because I had all the supplemental Forgotten Realms books, and so pages from The Mages, Prayers From the Faithful, Faiths & Avatars, Deities & Demigods, like all that stuff. I thought, let's include more druid spells, priest spells, wizard spells, and the spell compendiums. I know BioWare actually pulled from those for Baldur’s Gate 2. I threw everything I knew at it, which I think is one of the reasons why Icewind Dale and Icewind Dale 2 have a reputation for being pretty hard. This is especially true if you played the non-enhanced edition of Icewind Dale 1, as I designed all of that stuff to be played by super aggressive min-maxers. Most players are kind of min-maxers, but it was really like pushing it. So that was a lot of fun.

Fallout: New Vegas is highly regarded by fans of the series. What were some of the challenges and highlights you faced while working on this project, and how do you view its legacy within the Fallout franchise?

Making it in 18 months, that was a big challenge. You know, the other big thing was that none of us had used the engine before. So it was funny because we hired Jorge Salgado, whom Oblivion players would know as Oscuro. He was a modder, but when he came onto the team, we hired him as basically a junior designer, but he was actually the most experienced person with the engine when we hired him, because he had done all the modding on Oblivion. Learning how to use Bethesda's tools and gaining insights into how streaming and memory management worked. This was the source of many of our bugs because much of that information isn't clear until you approach the end of development.

And Bethesda has had years and years and years working with this tech. I would like to mention that Ashley Chang was extremely helpful to the extent that he could be. However, some things were lessons we had to learn on our own as we progressed. So that was rough. Same thing with the scripting system. Jorge was a huge help in helping us understand how the scripting system works. It's an extremely powerful scripting system, but its capabilities are such that you can inadvertently create many issues with it. As a result, there's a lot of scrapped content due to people saying, 'Oh, I bet I can do this with the scripting system.' It's a mix of yes and no, with some undesirable side effects. But I think that was really the big thing.

Then there were these weird things that we couldn't even explain. Like we put looping reloads in, so for the revolvers or the lever actions where you put in one round at a time, and that should be a really straightforward system. And it was, except that we kept getting bugs for literally the entire development cycle and it would go away and then it would come back, and they were not minor ones. They were really screwing up movement. And it was so frustrating because we tried to really restrain ourselves and only make changes that made sense. We knew we were doing it in 18 months, so we didn't want to do things that were really risky or likely to result in bugs. But there were a few things that, for whatever reason, we just couldn't figure out how to do or get right.

For example, the getting shot in the head sequence at the beginning was initially in-engine, not pre-rendered. What we did was look at the opening of Fallout 3 and the birth sequence. And it's kind of a reverse of the birth sequence, right? Instead of being born, you're being killed. But we wanted to ensure that what we were doing in the opening wasn't fundamentally different technically from what they did in the opening of Fallout 3. And we did, but it kept breaking. The scene just kept breaking. And we couldn't explain why. There was no apparent reason. Eventually, we had to pre-render it because we just couldn't get it to work. And I think it must be because we were not familiar with the engine. Yeah, so a lot of it involved technical challenges, but on the content side, we had a lot of really creative writers. We had a lot of great designers with a great scripting background. So they dove into the scripting language and they really did some incredible stuff. So I always felt like everyone was just making really good stuff every day. So I was really blessed to have the team that I worked with.

What were the main aspects that you brought into New Vegas from the cancelled project Van Buren?

Oh, there's a lot of stuff, although a lot of it is to be honest modified. Chris Avellone had been working at Black Isle for years on the Fallout Bible and ideas for Fallout 3. There were ideas like Caesar's Legion that came over, although my interpretation of Caesar's Legion was very different from the design in the initial documents. Characters like the Burned Man had a certain design within Van Buren, but then I changed it significantly for the endgame. Arcade was a character that I played in the tabletop game when Avellone was running sessions in his Fallout 3 campaign, and I made him a companion. And then there were just lots of other, I mean, it's been so long that it's hard for me to remember.

That's why I don't answer when fans ask me stuff online because it's gotten to the point where my memory is actually influenced by other people talking about it. And I don't even know if I'm telling the truth anymore. But yeah, there were a lot of big and small elements that we pulled over.

You're working at Obsidian, and now that you are all part of the Microsoft Studios family, would you be interested in working on another Fallout game?

Yeah, I mean, I think I've consistently said that. I think that would be really cool. I think the circumstances would have to be right for it because I got my chance to work on a Fallout game. And even though at release it was not super well received, over time it's grown in appreciation, for which I'm very grateful. I'm glad that fans do really enjoy the things that I thought were really good about it. And I believe the effort that the other designers put into it that made it feel unique and special while still being undeniably a Fallout game. So I feel like I fulfilled that, and I don't want to fuck it up, right? I don't want to just make a game for the sake of doing it. So yes, and I'll say this over and over again, I don't make these decisions. Stuff like this happens well above my head. I know I have a prominent position in the industry, but I'm just a studio design director. I'm not a studio head. I'm not Feargus. I'm not someone like Phil Spencer or anything like that. So yeah, I think that would be really cool if the circumstances are right.

As the project director for Pillars of Eternity, how did you approach the development of a new IP?

Oh yeah, that's an interesting one because that was the first IP that I developed professionally. But you know, even when I was a teenager playing D&D, I played and ran games in the Forgotten Realms, but my interest was in making my own worlds and settings. So I had done a lot of that in high school and college. This might sound weird, but I didn't find it particularly daunting. I just dove into it. I thought, 'Alright, let's start doing stuff and making things.' And the thing is in the Kickstarter phase, everything was happening so fast that it was a little too aggressive. We had to just make up ideas super quickly.

So like Orlans, Aumaua, those were created really hastily. I remember talking to people and saying, 'Okay, we're going to have elves and dwarves because I think people really would like to play those fantasy races. I don't think people are super attached to halflings or half-orcs specifically, but I think they like the idea of a little guy and a big guy.' I believe Avalon maybe had the basic idea for the Ciphers. Tim Cain had the basic idea for the Chanters, but it was all really rough. The initial map that I drew was not geologically possible, but it was drawn quickly because the Kickstarter campaign was so aggressive. It was crazy.

But once we actually got past that phase, and I was able to go back, we revised the map, clarified some stuff, and then it became more fun. I love world-building, and it was really enjoyable. The one thing that's tricky is when I'm world-building for my own tastes; that's easier than when I'm trying to fulfill the expectations of people who want a spiritual successor to the Forgotten Realms, which is such a big setting. So many designers have made so much stuff. So many writers have written so many novels, so many characters. So one person's idea of what the Forgotten Realms is might be very different. And the tabletop version is very different from the video game versions.

So, sometimes the struggle that I had is gritting my teeth about certain ideas that people really attached to but that I didn't think fit with the other parts of the setting. Although discordant, the setting's discordance is kind of part of the Forgotten Realms. It's like in the new D&D movie. So it's basically Guardians of the Galaxy meets Forgotten Realms, which is actually a pretty good formula, but it really highlights all of the goofiest stuff of the Forgotten Realms. I have run campaigns that basically don't say that stuff doesn't exist, but they don't look at any of that stuff. I pick and choose all the stuff that's a little more grounded, a little more serious, a little less silly because the setting is so big. You can do that. You can have content that feels much more grounded and less crazy, but you can also have stuff that feels like the D&D movie. My tendency is to usually go for stuff that feels more grounded. Even Icewind Dale is a pretty grounded space, but a lot of players, honestly, want over-the-top silly stuff. And sometimes, that was a struggle for me to reconcile.

Pillars of Eternity was crowdfunded, and the campaign was a significant success. How did crowdfunding influence the development process, and what lessons did you learn from that experience?

We expanded the initial scope quite a bit. One of the overextensions, which I knew at the time was really risky, was adding the second big city, Twin Elms. And I think that really hurt the pacing of the third act of the game. It's my responsibility, but I think adding in the third act, having another big city is not a good thing. We just shouldn't have done it. But the other thing was the stronghold; we knew we wanted to do something like that when we were pitching it. But when we got to actually technically implementing it, we couldn't do what we thought, like what we wanted to do; we couldn't do it technically. And that's one of the reasons why the stronghold, I think, was pretty disappointing for people in the shipped game.

I think Bobby Null did a great job later of adding all the stronghold events that were patched in. And also, the big plot line that came in with White March was really cool. So that definitely affected it. And then, yeah, just the sheer volume and passion of the player base, which we always knew they were there, but people have a lot of different opinions about what an Infinity Engine-style game should be. And those are not unified, but they're all quite loud and insistent. And so that sometimes, much like the world-building, whether it was the mechanics or the attribute scores, that was a huge headache to build that system. I've given talks on how complicated that was from my perspective. Some people would say, oh, just do D&D stats, which to me, wasn't good enough. So I had to like try my best to do something better, what I thought was better than that. And some players think that's stupid. Like you shouldn't have even bothered. But I'm like, okay, well, that's not how I design things. So yeah, there were a lot of challenges, but I'm really grateful that it saved the company, really. So we always have to be really grateful to the fans that they trusted us to make something that would be a good successor to the games that they remembered.

Pentiment is so different from your previous works. So, where did you draw inspiration for Pentiment from? And why did you decide to develop the game in a smaller team?

So the initial inspirations were historical games that had come before. Like Darklands, that was the first inspiration. But for Pentiment, I actually started getting the idea, I want to say, around 2018. And it was, I played Night in the Woods. My friend Scott Benson was one of the main people who worked on it. And I talked with Scott a little about how he approached it. That was a team of three people. And I knew I wanted to do something that was more complicated and would naturally involve a larger staff, but I knew it was not going to be that big.

When Microsoft acquired Obsidian, and I knew that they were really big on Game Pass, I went to Feargus, my boss, and I said: 'I basically got to do this. We got a bunch of other projects going on, I'm not going to take a lot of people.' I think, at the time, I said it would be maxing out at a dozen. It wound up being 13. But I said: 'I'm not going to take forever, I'm not going to lose a bunch of money, I'm not going to spend a bunch of money, and I think it'll be really attractive for Game Pass.' And they went for it.

The art style was pulled from a lot of historical woodcuts and late medieval illuminated manuscripts. And the story was inspired a lot by Name of the Rose and Andrei Rublev, those are the two big inspirations. But then the gameplay, if you look at how you navigate and explore, it's like Night in the Woods without the platforming. Obviously, it‘s a different art style. But even the mini-games, the super simple mini-games, are just there to break up the pacing and kind of give you a closer look at the world. They're not supposed to be challenging, they're not supposed to be complicated.

Actually the first one we did was the Ferenc's volvelle. And everyone thought that was too complicated. So we left it in, but every mini-game we made after that was much simpler and more for vibes than challenge. It was just supposed to be a fun little distraction. The cookie cutting mini game is probably the most popular thing that we made in it.

Are there any specific ambitions or goals you have for your upcoming projects?

Yeah, I got to really fully believe in it. I think after Pentiment, because I've worked on a bunch of stuff that I believed in to one extent or another. And this year will mark my 25th year as a game developer. And I think after Pentiment, what I found is I can't direct a project if I'm only halfway into it or don't truly believe in it. So whatever I do, I got to really believe in it. And also I know that I can't do it without a team that also doesn't believe in it. It's not all about me.

So, like Pentiment, not everyone is as into the stuff as I am, but they were into the idea of the game. So even if they weren't super big history fans or big narrative adventure people, they believed in what I was doing. They brought their own special stuff. Everyone brought their own special stuff to the game. But that to me is like the core of what it's got to be. Whether the game is big or small, it doesn't matter as long as I'm into it and my team is into it. That's the most important thing.